League Against Cruel Sports – 2025 Annual Review

100th Anniversary Edition

Some organisations mark a centenary by reflecting on their history, their principles and whether they still resemble the institution they were founded to be. The League Against Cruel Sports marked its 100th year by doing none of those things, preferring instead a familiar programme of silence, spin and the energetic collection of email addresses.

Founded in 1925 to end cruelty to wild animals, the League entered its centenary year apparently determined not to draw attention to either the founding or the animals.

January: Governance, Reimagined as Self-Promotion

The year opened with Chair Dan Norris enthusiastically fronting the League’s press releases, a bold reinterpretation of a role traditionally associated with oversight rather than hogging the microphone. This was an especially imaginative choice given the less-than-ideal publicity Norris was attracting elsewhere in connection with the West of England Combined Authority.

Still, if there is one thing the League has always believed in, it is leaning confidently into awkwardness.

March: The Arrival of Adult Supervision

By March, Emma Slawinski had arrived as CEO, a development that suggested even the trustees recognised there are limits to how much contempt you can show your own membership. After a year of acting arrangements and visible decline, even the trustees appeared to grasp that appointing Chris Luffingham as CEO would have been an act of such open mockery towards League supporters that it might not be survivable. And so, with evident reluctance, they did the unthinkable and appointed someone else.

This alone felt like progress.

April: The Power of Saying Nothing

April brought the small matter of the League’s Chair being arrested. The League responded with its trademark blend of silence and inertia. Norris did eventually resign, though as the role was unpaid, this represented less a sacrifice than a light diary adjustment. His salaried political roles, naturally, were another matter entirely.

What followed was not leadership but absence. Trustees Astrid Clifford, Ashleigh Brown and deputy CEO Chris Luffingham – all of whom had played a central role in reappointing Norris the previous year – carried on regardless, offering members no explanation, no accountability and no hint of reflection.

Either they were aware of the issues surrounding Norris and chose not to act, or they were not aware, which would raise rather awkward questions about how seriously they take their duties of oversight. The League did not clarify which applied, opting instead for a third option: say nothing and wait.

The charity preferred to let the moment pass quietly, like an awkward smell in a lift.

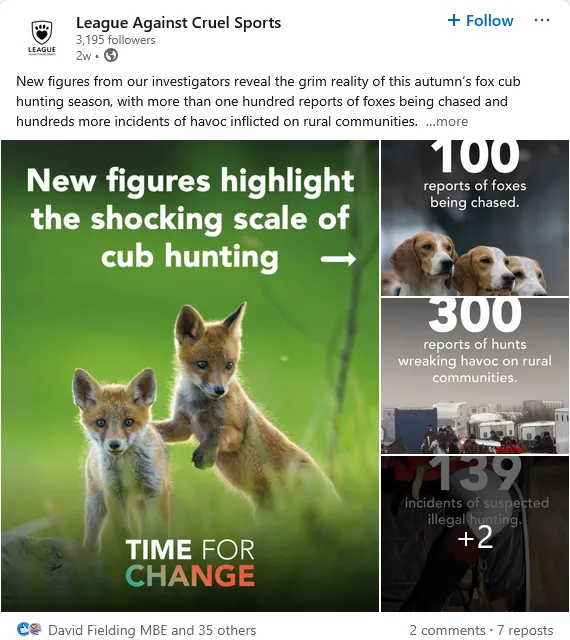

August: Cub Hunting, Brought to You by the Bullring

With the start of the cub hunting season, League campaigners sprang into action – primarily into Birmingham city centre. There, at a safe distance from hunts, hounds and anything resembling fieldwork, they conducted email-harvesting exercises occasionally marketed as petitions. These were sometimes enhanced by the appearance of a fox costume, lending the proceedings the air of a regional shopping-centre panto.

In the countryside, monitoring continued largely by hunt saboteurs and independent groups, while the League perfected the art of appearing industrious several counties away.

Awards Season: A Moment of Clarity

The League, clearly delighted with its new CEO, “nominated” Emma Slawinski for a CEO of the Year award, this despite Emma being employed for just three months.

September: AGM as Sleep Aid and the Great Reset

September saw the League repeat its innovative AGM format: hold it on Zoom and hope no one notices. Around 20 members tuned in, a turnout best described as intimate. The meeting was widely praised for its soporific qualities, with at least one attendee reporting improved sleep patterns.

At the same time, the League unveiled its latest corporate concept: the Reset. This was presented as a moment of renewal, reflection and accountability, prompted by the minor administrative inconvenience of the Chair having been arrested earlier in the year.

As part of this Reset, the League advertised for a new Chair, signalling a fresh start grounded in transparency, independence and robust governance – at least in theory.

At the AGM itself, Astrid Clifford was presented for re-election as a trustee in tones normally reserved for moral exemplars. It was a polished performance, illustrating just how adept the organisation has become at reassuring members while disclosing as little as possible.

The League also published its 2024 accounts and Trustees’ Report. Conspicuously absent was any reference to Dan Norris, despite the considerable efforts made by trustees to reappoint him the previous year. This selective silence sat comfortably alongside the rhetoric of renewal.

Figures were also released on the scale of cub hunting uncovered by “our investigators”. It later emerged that “our” referred largely to other organisations. When this was pointed out, the League – freshly reset from previous inaccuracies – chose not to correct the record.

November: Appointments and Amnesia

In November, the League concluded its search for a new Chair by appointing David Fielding MBE. The appointment was presented as the culmination of the Reset: a clean break, a steady hand and a reassuring signal that lessons had, at last, been absorbed.

Fielding is new to the role, and time will tell how he chooses to exercise it. Some observers noted that he had previously spoken warmly and publicly about Emma Slawinski during her time at the RSPCA, a perfectly respectable professional familiarity that nonetheless places an early test before him.

Charity Commission guidance is clear that trustees must be, and be seen to be, independent of the executive. It will therefore be interesting to see how the new Chair manages that relationship in practice, particularly in a charity where scrutiny, accountability and transparency have lately been treated as optional extras.

Later that month marked the actual centenary itself: 25 November 2025, one hundred years since the League’s inaugural meeting at Church House, Westminster. The date passed without acknowledgement from the organisation that owes its existence to it.

More than 50 supporters gathered independently to mark the anniversary. No League staff attended. The League’s website and social media channels ignored not just the event, but the centenary of its own founding altogether. The moment went unmarked, unmentioned and apparently unworthy of notice.

For a charity reaching its hundredth birthday, the message was unmistakable: please don’t make a fuss. There was, after all, no obvious fundraising angle.

December: Resilience Training and Database Building

By December, campaigners were back in city centres following a two-day resilience training course. Armed with Time For Change placards, they resumed the essential work of collecting email addresses, occasionally interrupted by mentions of hunting.

Awards Season: A Moment of Clarity

Emma Slawinski won the Female CEO of the Year for the Best Animal Welfare Charity in 2025 award, prompting the League’s media operation to reawaken abruptly. Press releases were issued. Social media stirred. The centenary briefly intersected with good news, which is always worth amplifying.

If only the League’s founders had thought to collect awards rather than confront cruelty, they too might have been remembered in the centenary year, instead of quietly erased by an organisation now far more comfortable celebrating itself than the change they actually fought for.

The Century Mark

And so the League Against Cruel Sports completed its 100th year: an organisation founded to confront cruelty now defined by avoidance, opacity and the disciplined refusal to account for itself. There were no explanations, no reckoning and no serious attempt to engage supporters or donors in how decisions were made or why.

A century on, the animals are still waiting. So, increasingly, are the people who fund the League, support it and are entitled to expect honesty in return.

Here’s to the next hundred years – ideally with fewer fox costumes, fewer silences, and rather more courage.