When Principles Are Selective: Point-to-Points, Hypocrisy and the League Against Cruel Sports

The League Against Cruel Sports is right to condemn point-to-point racing.

These events are not quaint rural fixtures, nor are they politically neutral sporting occasions. They exist to raise money for hunts, to normalise hunting culture, and to present an air of social respectability around practices that the vast majority of the public now regard as cruel and anachronistic. When the League publicly criticised Jeremy Clarkson’s Hawkstone brewery for sponsoring the Cocklebarrow Races, it was acting entirely within its remit — and, more importantly, in line with its founding purpose.

Point-to-points do prop up hunting. They do fund hunts directly. And the attempt to cloak them in nostalgia, celebrity endorsement or rural charm is precisely the kind of deception that animal welfare organisations exist to challenge.

But principles, if they are to mean anything, must apply inwardly as well as outwardly.

In January 2019, The Telegraph reported that Martin Sims, then the League’s Director of Investigations, had attended several point-to-point meetings — events explicitly organised to further the interests of hunts. One of these was the Cornwall Hunt Club point-to-point at Wadebridge; others included meetings linked to the Dart Vale and Haldon Harriers. These were not obscure technicalities. Point-to-point rules themselves state that when organised by a hunt, such events must include “the furtherance of the interests of that particular Hunt or Hunts in general”.

In other words, the very activities the League now condemns as lending “a veneer of respectability” to cruelty were being attended by one of its most senior officials.

This was not merely an unfortunate optics problem. It was a clear conflict of interest.

Sims was not a junior employee with little influence over policy. He was Director of Investigations — the public face of the League’s enforcement work, leading covert surveillance of hunts, and publicly denouncing fox hunting as “barbaric” and a “dark and menacing blight on the countryside”. That same official was, at the same time, present at hunt fundraisers.

The League stated at the time that Sims attended these events in order to protect his daughter, who was pursuing a career as a jockey and had received threats and abuse. That explanation deserves to be acknowledged. Any parent would be concerned for their child’s safety, particularly in an environment that had become increasingly hostile and politicised.

But understanding a motive is not the same as resolving an ethical conflict. The issue was never whether Sims cared about his daughter — it was whether a senior official of an anti-hunting charity should be attending events explicitly organised to fund and promote hunts, regardless of the personal reasons given.

Where such a conflict exists, responsibility lies not with instinctive parental behaviour, but with governance. Trustees and senior management had a duty to recognise that attendance at hunt fundraisers by the League’s Director of Investigations — a highly visible role central to its credibility — was incompatible with the organisation’s stated principles. If attendance was unavoidable, the ethical response would have been for Sims to step aside from his role, not for the League to redefine the problem out of existence.

The explanation also fails to account for the wider context. To compete in point-to-point racing, a horse must be registered with a hunt and its owner must pay a hunt subscription. Records showed that the Sims family horse was registered with the Tiverton Staghounds — one of only three remaining packs of staghounds in the country.

This detail matters.

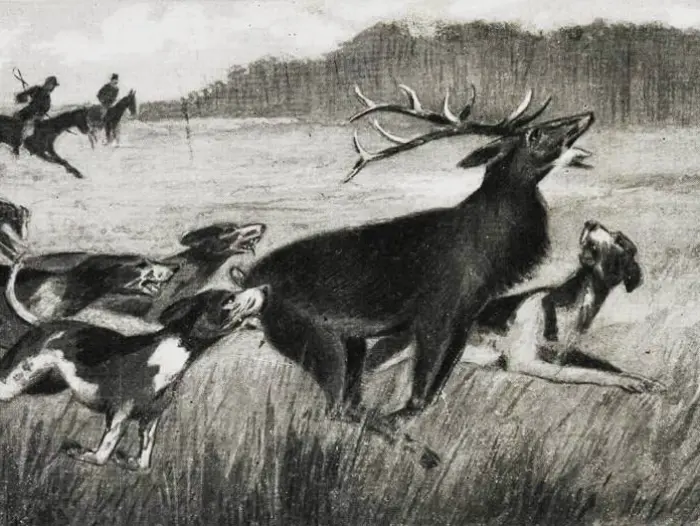

The League has long and rightly focused on the particular cruelty of stag hunting. It owns land in the West Country specifically to protect deer and stags from being hunted to exhaustion before being killed — a practice the League has repeatedly highlighted as among the most brutal forms of hunting. To have a senior official’s family financially connected to a staghound pack is not a marginal inconsistency; it cuts directly across the organisation’s campaigning claims.

What is most striking, however, is not Sims’ personal decision, but the League’s institutional response.

Rather than recognising the conflict of interest and insisting that it be resolved, the organisation chose to defend the indefensible. In doing so, it asked supporters, saboteurs and the wider public to accept a double standard: that point-to-points are reprehensible when attended by sponsors and celebrities, but excusable when attended by senior League officials.

At the time these events occurred, Astrid Clifford was a trustee of the League. Many of the directors in post then — including Deputy CEO Chris Luffingham — remain in senior leadership today. This was not a failure of one individual; it was a failure of governance.

Trustees exist to safeguard a charity’s integrity, not to smooth over ethical contradictions. Silence, in such circumstances, is not neutrality. It is consent.

The irony is that this hypocrisy sits uneasily with the League’s own history. Opposition to stag hunting is not a recent branding exercise or a convenient campaigning angle. It is foundational.

In 1935, Henry B. Amos, co-founder of the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports, protested inside Exeter Cathedral against a stained-glass window glorifying a stag hunter responsible for the deaths of thousands of deer. Amos described stag hunting not as sport, but as “sustained agony”, carried out for pleasure and therefore “a crime against man and a sin against God”. He was arrested, imprisoned overnight, fined heavily — and unrepentant.

Henry S. Salt, one of the most important figures in the humanitarian movement and a formative influence on the League’s ethos, publicly praised Amos for his courage. Salt regretted only that he himself had not broken similar windows sooner.

This was a movement willing to confront respectability head-on, to reject the polite accommodation of cruelty, and to accept personal cost rather than compromise its principles.

Measured against that legacy, the League’s indulgence of point-to-point attendance by a senior official looks less like pragmatism and more like moral drift.

None of this undermines the legitimacy of calling out Clarkson, Hawkstone or any other sponsor of hunt-linked events. On the contrary, it strengthens the case — because credibility is built on consistency. A charity that condemns cruelty must be seen to refuse it, even when doing so is uncomfortable, inconvenient or personally awkward for those within its own ranks.

The League’s 2024 trustees’ report speaks of exposing deception and unmasking a “veneer of respectability” around hunting. That language is well chosen. But veneers are most dangerous when they are applied internally.

If the League Against Cruel Sports wishes to reclaim moral authority — not just rhetorical force — it must demonstrate that its principles are not selectively enforced, that conflicts of interest are confronted rather than explained away, and that trustees understand their duty is not to protect reputations, but to protect the cause.

History shows what moral clarity looks like. The question is whether the League still recognises it when it sees it.